As far as we know Shakespeare never wrote a solo. Well there are the poems of course. From time to time some brave actor has a go at the sonnets – an enormous challenge, and there are the narrative poems: Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece and the shorter, The Phoenix and the Turtle and A Lover’s Complaint – you seldom see these last named because if they do get an outing it’s usually a semi-desperate actor struggling to come to notice in one of the further-from-town venues at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival.

Of all playwrights Shakespeare is surely the hardest to destroy.

By which I mean, although it is distressingly easy to act Shakespeare badly, even when poorly done, something of the essence survives and makes the show worth seeing. Well having said that, I can think of at least one stand out exception at a major institutional theatre. Oh, alright more than one – but even in the worst of The Bard, you can close your eyes and forgive any shortcomings in diction, articulation and breath-support and imagine what your favorite actors would have done with it, can’t you? And if you do that, you can get drunk on the language.

Bad Shakespeare is, I admit pretty disturbing. But think of Shaw badly done, or, I will go further, Ibsen, nay, Pinter. When these masters are chopped up by practitioners that never found the rhythm, the result is often narcotic.

But when Shakespeare is well done … ah, that’s the stuff.

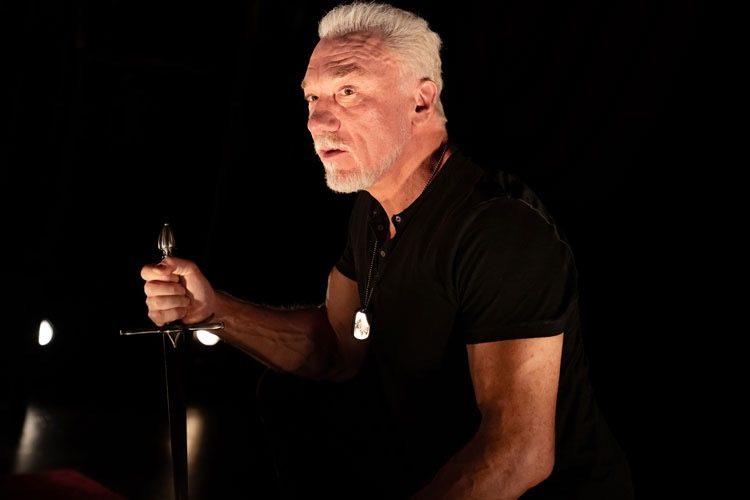

All this is a long preamble to me saying kudos to Patrick Page who has brought us a solo titled, “All the Devils are Here”. The show is an amalgam of theatre lore, well-chosen villainous Shakespearean soliloquies, (with a dash of Marlowe as a celebrity guest) and everyday chat nicely sprinkled with humor.

I persuaded Trish to accompany me on a visit to NYC to watch “All the Devils Are Here.”

It was fabulous.

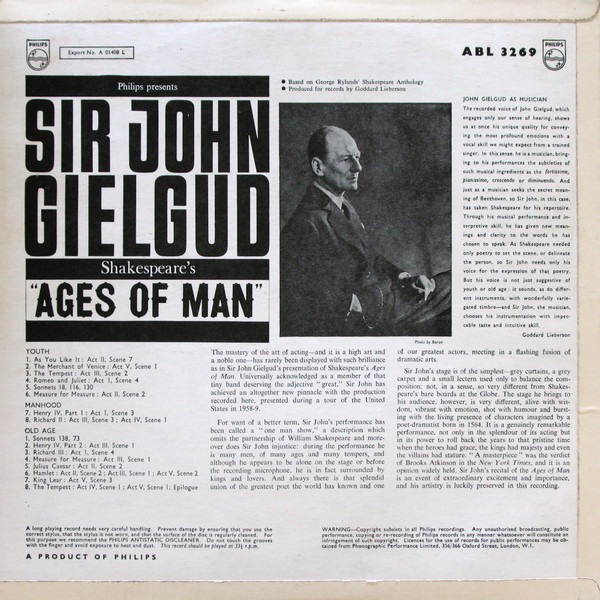

I had been apprehensive. Sir John (Gielgud) has set the bar (his “Seven Ages of Man” solo) at a height to which few of us can aspire. Although his voice in recordings now sounds firmly rooted in its period; for diction, articulation, breath-control and above all, economy of expression, and once you get through all that, for the simplicity and the force of his characterizations, he stands alone.

Sidebar here: I saw “The Motive and the Cue” in London a few months ago. It has now transferred from The National to the West End, and there has been an announcement that it is hoped to bring it to New York.

The play treats on Gielgud directing Burton in Hamlet in 1964 on Broadway. A fabulous mixture of theatre gossip, and two actors divided by a mutual love of language and all that it can do. If the play does make it over here, run don’t walk for tickets.

But a solo Shakespeare? I half expected to have that experience that Peter Brook describes in his book, The Empty Space, that is to say, mouthing the words of the soliloquies that one half remembers, at the same time being mildly bored because of indifferent delivery from the performer on the stage.

Not a bit of it!

Patrick Page, who is a quality Shakespeare veteran was supported by an excellent production in terms of the lighting, set, and direction as well as his own superb skills as an actor, including a lean physique and strong baritone. His phrasing approached Sinatra-like detail and his vocal variety was finely judged. The show came in at 80 minutes which I think is clever. At 60 minutes the audience has fully tuned in and is thinking, “this could go on for a while” but at ninety minutes, the audience starts to look at its watch.

As well as all that, we had the New York City cosmopolitan experience of running into two dear friends, Carol and Bob, one friendly director, Gus Kaikonen, and a friendly actor Walker Jones – so there was theatre schmooze as well.

If you have Bardic leanings, I highly recommend this show, and even if you don’t!