With great sorrow I write to commemorate the passing of Barrie Hesketh. He was a mentor and a friend and my first employer in theatre in 1983. He will be buried on the island he loved on Friday 19th December 2021. He is survived by his beloved second wife Philippa, his three sons, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

I was enormously fortunate to have my first professional job as an actor at The Little Theatre on the Isle of Mull in the Inner Hebrides. This was the theatre that Barrie and his late first wife Marianne ran together for more than 20 years, raising their three sons there. This is the letter I wrote to him two days before he died.

Dear Barrie,

Just a note my dear old friend and mentor …

I just want to tell you, I think you know, but this just to say how important you and Marianne have been in my life. Your wonderful example of enterprise and courage and spirit of fun, have stayed with me throughout what is now a 40 year – one can’t exactly call it a career – more of a stagger – on various stages.

I’ve had the most wonderful time of it. I’ve played from the Hebrides to N.Z. and back, on Broadway, off-Broadway, at The National, in Israel where I had pickled fish for breakfast, and in Beijing where I had strange culinary adventures. And through all of it I have been a proud Mull Little Theatre company alumni, frequently recounting tales of your theatrical achievement in dressing rooms across the States, Australia and anywhere where people would sit still long enough to hear of it.

I’m so glad of your long partnership with Philippa and if the Great Stage Manager in the sky is shortly to call “Beginners”, I know that you will leave much love here behind you.

You made a great, unique contribution to the British Theatre. One that was an inspiration to many. I still have hopes for the film, I only wish I had managed to get it done, but you may find yourself watching from the other side…

With huge admiration, enormous gratitude, respect and much love,

Colin

In 1990 I wrote a piece describing my experience on Mull and it was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in the UK. In response there was a large mailbag from the public many of whom had seen performances at The Little Theatre.

I publish this piece below. I hope it conveys something of the magic of the time and the place and of the extraordinary creativity, resourcefulness, and courage with which Marianne and Barrie took their work to the world.

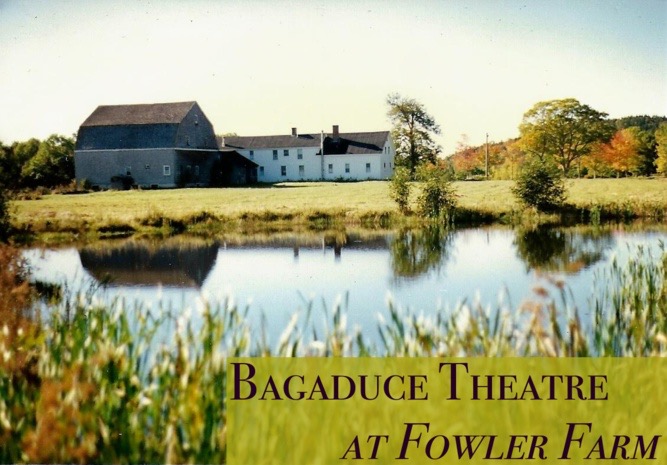

Another dear friend in the theatre has also died in these past weeks. John Vivian known to many as the long-time Broadway stage manager of Rent and other shows. John also ran a theatre with his wife Monique who survives him. The Bagaduce Theatre is the theatre which is furthest north on the east coast USA before you hit the Canadian border.

Like the theatre on Mull, is is physically remote. It’s in northern Maine. Like the theatre on Mull it offers great quality in its work, and like the theatre on Mull it took, as most theatres do, enormous flair and inventiveness and determination to run it.

John was a man of consistent gentle positivity, and complete dedication to the art. He died too suddenly and totally unexpectedly. Barrie had a long old age. I imagine these two very fine men of theatre have now met on the other side of the curtain. I know that they would like each other, that they would have stories to tell each other, and understanding to share.

Travels With Henry

If you’re an actor you may not be able to remember your last job, but you always remember your first one. While I was at drama school in London, I put together a one-man version of Shakespeare’s play Henry V. I knew there was a theatre on the Isle of Mull in the Hebrides, I knew it was just outside the village of Dervaig at the western end of the island, eleven miles from the nearest bus stop. I thought this might be the place to start off.

I wrote to the people who had lived and worked there for twenty years, asking them if there was any chance I could play my one-man Henry V at their theatre. Barrie and Marianne Hesketh were making a rare visit to London to collect their M.B.E.s (Member of the British Empire). We met at the Central School of Speech and Drama, where I was training, and where they had trained in the days of the school’s residency at the Royal Albert Hall. They were both then about fifty years old. Barrie had the air of Prospero on a bad day, thick silver hair swept backwards from a craggy forehead. Marianne looked like Judy Garland might have looked if she had gone on to bake a lot of chocolate cakes.

They began talking at once. Their conversation was not easy to follow, because they spoke as twins speak, dovetailing thoughts and sentences. I felt the conversation was going well, and I listened attentively, keen for employment. I slipped my hand into my pocket.

“You don’t smoke, do you?” asked Marianne. “We always ask,” she said.

“No,” I said. And I left the cigarette unseen in its packet. They asked if they could see me do something, and because there was never any space at the Central School of Speech and Drama, I took them to the car park, where I lustily summoned a muse of fire. It began to rain. The audition was a success—they offered me a job. It meant giving up smoking, but it was a job and it brought the treasured Equity card. I bought an old leather trunk for my props and an old green car to carry them in. I gave the car a name, because I knew that a car will run for you if you love it. I called the car Henry and the clutch went. I got the clutch fixed and called the car Molly, and we’ve been friends ever since.

It was May when I arrived in Oban in the Western Highlands and took the ferry across the Firth of Lorn to Mull. At that time of year the rhododendrons are in full bloom. I drove the long way round the island, my vision assaulted by the vivid pinks and purples, until I came to the theatre valley. Looking over the valley, there was no sign of a theatre or any habitation. The theatre stood on a Scots acre, and a hundred years ago the minister who had lived there had planted his land with broadleaf trees— alders, limes, and beeches, and at the front and back gates to the property, a rowan tree. Amongst the trees where the Heskeths had raised their family and on the other side of the acre was the byre where the minister had kept his animals. This had now become the smallest professional theatre in Great Britain.

In one half of the byre, a horse had lived. That become the auditorium. The other half, once a cow’s dwelling, had become the stage. There was seating for thirty-seven people—at the back a long bench with cushions; at the front six low-slung easy chairs with springs long gone; in between, stalls from an old cinema. The six rows of audience slanted from stage level at the front to roof level at the back. The stage was ten feet wide by fifteen deep, covered with corn-colored rush matting, well-worn, and complete with wings, flies, black, tabs, one entrance stage right, and one more upstage center. It was a theatre in miniature.

The day I arrived, Barrie and Marianne were at dress rehearsal stage for their new play, Ostrich, a two-handed piece they had written themselves. Together they had attempted everything from William Shakespeare to Michael Frayn. Some years they employed other actors and one year the company had been as huge as five. Usually they found ways to fill their stage with characters alone—this season included a two- actor version of The Importance of Being Earnest. After so long constantly working together they had a rapport that was fascinating to watch.

During a tea break, Marianne jokingly explained that she’d had a mastectomy. “It’s the left, no the right one,” she said, patting each side as if not really sure. I almost believed that she could have forgotten, but a few weeks later, as we were drinking gin after the show, I asked her about the illness. She said she could cope with it, and as regards dying she “made here arrangements.” The suddenly, “I hate the mutilation.” When she said “hate,” her lips trembled and tears came to her eyes.

The season opened with a performance of Ostrich. It was a comedy set in academia. The theatre was full. A first-night atmosphere, a party. There were friends, holiday makers, the milkman, and Betty. Betty was an indomitable lady of robust old age who lived with two boisterous Dalmatians and lots of ducks in a well-kept cottage where she painted flowers. In her blue mini, she sat ramrod straight and drove at speed around the island. When she arrived at the theatre, she called “Hello dear,” to whomever she met. She was the theatre’s honorary grandmother, and she always brought duck eggs.

The performance was a success. There was only one interruption when a flock of sheep passed by the west wall of the theatre and I was sent to chase them away. This became part of my job during the season. When the audience had gone, Barrie and Marianne said, “We’re open!” There was a terrific sense of achievement and off they went for the post-show drink of gin and orange juice.

A few nights later I had my own first night with Henry V. It was my first professional performance and I was nervous to the point of nausea, but Marianne said, “The theatre’s on your side, Colin, it’s just told me.” I believed here. The show lasted ninety minutes and there fourteen people in the audience. The idea was to start with a bare stage and end up with it covered in the debris of the story. There were puppets— three-quarters life size for the bishops, finger puppets for the heralds—a cigar puffed vigorously for the cannon and the smoke of war, a bicycle, lots of hats, a parasol, flags, streamers, confetti, and a custard pie. I made a lot of mess. When it was over, Marianne came round and embraced me, and they took me to their kitchen for supper.

“An egg?” asked Marianne.

“Two,” said Barrie. “He needs two eggs.” And we drank gin.

A one-man version of Henry V is not an easy show to sell in the inner Hebrides. To begin with, the audience figures were not encouraging. Fourteen, eleven, seven, five, three. The night I played to three people, two of them were French. I tried everything I could think of to sell the show. I put posters up around the island with adjectives like “Dazzlingly bold!” and “Boldly dazzling!” Once I went to the main town Tobermory, and stood in the street wearing a silly hat and juggling tennis balls. A policemen came and watched me. After a time he said, “And tell me, do you just stand there and play with your balls?”

At last I hit upon something to improve sales. For some reason I had a suit in plum-colored velvet. It didn’t fit very well. No matter, I bounced onto the state one night wearing this costume, juggling tennis balls, and doing my U trailer.

“Ladies and Gentlemen, your attention please! This is a U trailer, for yes! You’v guessed it! A U-certified version of Henry V. Shakespeare on a budget and as you’ve never seen him before. I play all the parts—several thousand—don’t forget the two armies! It’s here, it’s now, it’s alive, it’s happening in the smallest theatre in the world. Book now to avoid disappointment!” People liked this, and within a few days the bookings for Henry were much improved.

After a few weeks a routine of life emerged. In the mornings the three of us would meet for coffee. Barrie and Marianne concocted a brew of such strength it made you teeth shake, and they drank a lot of it. After coffee, it was administration. Neither of the Hesketh’s were administrators by nature or training; they did things twice, three, or four times when once would have done. under pressure Barrie had the habit of producing a sound like a snorting whale. He was a widely gifted man. A painter, a musician, a writer, and an actor. For twenty years he had put bread on the table by working on the stage. After lunch he would paint water colors which he sold in the theatre, and the more outrageous he was about them—”I think I’ll do this one in mauve”—the faster they sold. Marianne made chocolate cakes and had ideas. She thought and spoke at a great rate and had a well-stocked and scatty mind, “You could come back next year and we’ll do Hamlet or Sleuth. Are you going to tour for us? Have you read Gordon Craig?” Then there were the Little Theatre histories. The two-handed Tempest, how Olivier had nearly made it to a show, how Scofield used to come. In the evening, we would go into the theatre an hour or so before the show, lay out a display of cookbooks, bookmarks, and chocolate cakes, and spray the dressing room, foyer, and front and back stage with insect repellent in the endless battle against the Mull midges which have boots on. This was important, as occasionally you’d find a midge on stage with you and there was nothing to do except let it graze happily.

Before long it was June, and the rhododendrons lost their blooms, the yellow gorse appeared bright as acrylic paint. I got to know the island. Neither Barrie or Marianne could drive, so I used to run the errands to the shops, to the bank. When free to explore, I wandered in my old green car. There was the ancient oak forest at Torloisk, the sandy beach at Calgary which is washed by the warm gulf stream, I met Nellie who lived like a guardian at the site of the petrified tree. I met an artist from south London who lived in a remote cove. When I asked him what had brought him to Mull, he said, “Magic. Nothing more, nothing less.”

Iona, where I toured in July, was different again. A quarter mile of water separates it from Mull. The cloud in the region goes to Mull and the mountain. Iona is sunlit. I had to get a special permit to take the landcover across to carry my props. One of the ferrymen came and looked at me. He was a big Glaswegian, as broad as tall, ice-blue eyes and a long knife scar in his throat.

“And what are you going to do on Iona?”

“I’m going to give a performance at the Abbey.” “Is it just yourself like?”

“Yes.” He looked at the sea and thought for a moment. “Now let me get this straight, it’s just you, no one else, just yourself?” “Yes.”

Thought. Silence. Then, “That doesn’t sound fuckin’ right to me.”

I performed Henry on the altar steps of the old Abbey lit by three spotlights. There was a gale outside, and twice the west doors burst open and the wind came howling down the nave.

Back to the Little Theatre. Now the season was in full swing. A profusion of wildflowers colored the hill behind the theatre, and the place was full every night of the week. Sometimes as many as forty-eight people—well over a hundred percent capacity. The audience came from everywhere. Once, nine people came in an open boat from the isle of Muck—two hours at sea. I played Henry V to a party of schoolboys from the famous Public School at Stowe. There was a mountain man from the American Midwest; there were the local landed gentry. I don’t know what Marianne put in the chocolate cakes, but everyone seemed happy. When there was a power cut one night during a performance of Chekov’s one-act comedy The Bear, people in the audience willingly follow-spotted us with torches. “You wouldn’t get this at the RSC,” said Marianne.

At the end of the month, when the gorse yielded to the foxgloves pointing upward like spears of fire, I decided to climb the mountain Ben Moore. Ben Moore is supposed to be the home of the wizard of winter who shows his presence by laying a finger of cloud on the peak. I came within fifty feet of the summit. I stood looking along the line of watershed fearing to lose myself in the mists that came and went so suddenly. from there, over the wide landscape, the moss on the rocks the color of salmon flesh, it seemed to me there was a tougher feel to life than in the soft south of Britain. At last, offering my respects to the wizard, I climbed down, knowing that I would return to Mull. The island is littered with standing stones, remnants of an ancient time when earth magic ran vigorously through the land. Now and then you’d happen upon some secret place in the hills or the forests where the little folk live. And there were the faces in the trees. The features were easier to see at dusk, and in the fading light the trees became totem poles. There was prescience in the ether.

A few years previously the Little Theatre had produced Macbeth using puppets. Although the production had been very successful, the Hesketh’s had no fondness for it because it had been then that Marianne had been attacked by a second cancer. They subscribed to the superstition that surrounds this play. When I arrived there was no active cancer in Marianne’s body, but somehow we all knew it would come again. In August I took her to be X-rayed at the island’s hospital. A tumor was discovered in her spine.

Afterward, as we drove along the valley which was exploding with purple heather, she asked, “Did you know?”

“Yes,” I said. “Did you?”

“Yes,” she said. We drove home in silence.

Marianne went to Glasgow for radiotherapy. Barrie and I were alone at the theatre for two weeks. We did programmes of verse and stories and on-act Chekov plays, and on the weekends, while Barrie went to visit Marianne, I did Henry V and Betty came with duck eggs. After Glasgow, Marianne went straight back on stage. Radiotherapy can be a shattering treatment; sometimes she was quite literally pale green waiting in the wings of the tiny theatre that had been her home for twenty years. She’d go on stage and the pallor would fall away. It was an example of courage in the theatre that I will always remember. Her method with the disease was to outface it with stubborn disregard, and, to the last her mind was full of plans for the future. “I’ve written to the National,” she said, “I’ve told them I’ll do anything. In my condition I could play an Amazon, or I could have the other one off and they could strap a sword to me and I’d carry a spear.”

Barrie would make loud defiance. “She’s not dead yet.” he shouted more than once.

The season ended as it had begun with a performance of Ostrich. The colors in the hills were different, the blood red of the rowan berries now dominate. It was Marianne’s last performance there. The theatre was full, a party atmosphere. Afterward, Barrie called me on stage; I entered with a bouquet of flowers and a bottle of champagne. I made the following speech as I poured the three of us a glass: “Ladies and Gentlemen, it has been such a special summer for me and the realization of a long-held ambition to work at this theatre. I give you the Little Theatre!” And the audience chorused, “the Little Theatre!” And there was applause. When they had all gone, we lingered in the foyer making extravagant compliments to each other in the way that actors do: “Darling, you were marvelous!” Then we went over to the kitchen for a final supper of eggs, salad, and gin.

Marianne’s health and been deteriorating daily; her spine had weakened to the extent that she found sitting down and getting up difficult. Everything was re-worked so that on stage she was always standing, and in this condition she and Barrie went on to complete a six-week tour in Europe. Previously, on a dozen British and half a dozen European tours, they had employed someone to drive them. But this time they went by bus and train as they progressed through the one night stands. Marianne could walk, but she couldn’t carry anything, so Barrie carried all the luggage, and all the props and scenery as well.

Anyone who met the Heskeths will remember them and their theatre, but I remember them for their kindness and their courage and for my first job. A final image stays with me. A few days before I left I found a sea bird with a broken wing. I put it in a box and few it Weetabix. In time the wing healed, but the bird had lost its confidence in flight. Months later, Barrie wrote and told me how he had taken it to a cliff above the sea and thrown it high into the air. For a moment it had dropped like a stone, but then flapped its wings, happy to be free once more.